Jim Taker, c1822-a1887

aka Cheong Tak, Ovel, James Ovel, James Teager, James Teaguer, Ah Coe, Ah Tick, Ah Tak?

Sections

Cheong Tak

Indentured Labour

Ovel in Mauritius

Ovel in Van Diemen’s Land

Ovel to James Ovel to Jim Taker

Little Bendigo

Prison

Ah Coe, alias Ah Tick?

Back to Jim Taker

1885 – A Reappearance?

Footnotes

Discovery

Jim Taker was my great-great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side and the patriarch of the Taker/Teager/Teaguer family in Australia. Unfortunately, the surname is now extinct after three generations as, of the two male children, James had no children and Edward’s children were adopted by his widow’s second husband. For a detailed analysis of the evolution of the surname, see The Teager Name.

My journey of discovery first found a James Teager in the Victorian Birth, Deaths, and Marriages indices, then on the marriage certificates of his daughters Victoria Julia (my 2x great grandmother) and Mary Ann Edith from 1873. Both women married Chinese storekeepers from Amoy (Xiamen) on the same day. My mother had mentioned that her great-aunt Maude – one of Victoria Julia’s daughters – had identified as Maude Teaguer. This was confusing as Teager/Teaguer was her mother’s maiden name. Anyway, there were James Teager and Ellen Farrell as the parents of the brides. They were also listed on the marriage certificate of a third daughter – Ellen – in 1875, when she married a Cantonese storekeeper. The elder Ellen’s death certificate from 1905 said that she was born in Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland, was 80 at her death, and had been in the Colony of Victoria for 51 years (so arriving in around 1854). Without further investigation, Teager sounded like an Irish name to me so it was a fair assumption that James was Irish and had married an Irish woman.

It was then puzzling to not find any further trace of James and Ellen Teager/Teaguer at first. The revelation that this James Teager was Chinese and was known in Australia as Jim Taker started to make sense of all this and helped open so much research [01].

Cheong Tak

Indentured Labour

(More coming soon.)

Ovel in Mauritius

Oveil was tried at the Port Louis Assizes, Mauritius, on 28 November 1843 and sentenced to 10 years’ transportation for robbery. He is described a potter from the “Ahoun” “parish” of China. He is 30 years and 6 months old (all of the prisoners seem to be so many years and 6 months old), 5 foot 2 inches (157.5cm), with copper complexion, black hair, black eyes, and a scar on his right eyebrow. His character is described as “bad” – but then all of the prisoners are described as “bad.”

Ovel was tried at the Port Louis Assizes on 2 December 1843 and sentenced to life transportation for robbery and assault. He is described as a labourer from “Alak” (or “Alake”) “parish” of China. He is 21 years and 6 months old, 5 feet 4 inches (162.5cm), with copper complexion, black hair, black eyes, and a scar (cicatrice) on his left thumb. And of course his character is “bad.” This is our guy.

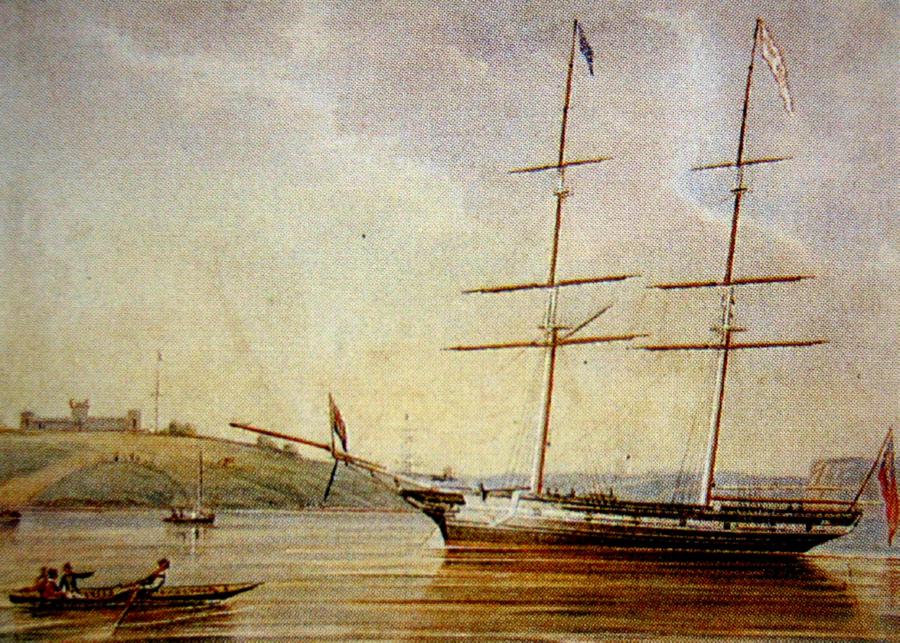

With the small numbers of prisoners transported to Van Diemen’s Land from Mauritius, transportation used ships that regularly stopped in Mauritius and Australian ports, rather than dedicated convict ships. In this case, it was the fairly new brig Ocean Queen, 192 tons. Built in Ipswich, Suffolk, in 1841, the Ocean Queen regularly sailed between ports in the Indian Ocean and Australia.

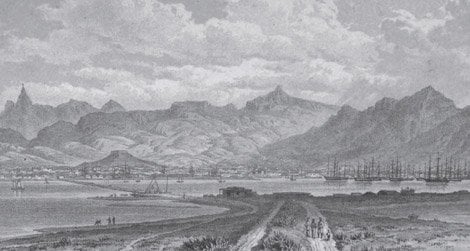

The Ocean Queen had arrived in Mauritius after sailing from Sydney on 23 October 1843 with cargo “and several passengers of the labouring classes” via Port Adelaide. During the stop in Port Adelaide, the Adelaide Observer had noted that:

Captain Freeman of the Ocean Queen, who is a South Australian landed proprietor of some years’ standing, has been visiting his estates, and inspecting the surrounding Districts; he has warmly expressed his surprise and gratification at what has been accomplished within a few years; and other visitors from Britain and the neighbouring Colonies have been equally delighted with our progress and prospects [03].

Ovel in Van Diemen’s Land

After discharging the convicts, the Ocean Queen continued to Port Jackson (Sydney) with its paying passengers and cargo, arriving on XXXX. It later sailed for London on 14 July 1844 carrying “colonial produce.” The image on the right is dated “c1841,” but is more likely to have been painted during the ship’s 1843 or 1844 visits to Port Jackson.

On arrival in Hobart Town, the convicts were processed. An entry was created in the “Conduct Register of Male Convicts arriving on Non-Convict Ships or Locally convicted” and several other registers for each of the male convicts. Jim was recorded as Ovel and given prisoner number 279. Oveil was given prisoner number 272, but his name was transcribed as Oreil in the Conduct Register and other documents, though he was still Oveil in at least one. This is how he was generally known in Van Diemen’s Land, though entries in the Hobart Town Gazette have him as Oriel [06]

It seems that, on arrival, each prisoner was asked what their offence was, rather than their conviction, and their answer was included in the register. Ovel stated that he had killed his “master” with a blow to the head. He was convicted of assault and robbery.

[More detail to follow. Ovel absconded in November 1853.]Meanwhile, Oveil was released in December 1853 after having served the ten years of his sentence. The Comptroller-General of Convicts, John Stephen Hampton , authorised the following Gazette notice (as Oriel) on 24 December, 1853.

There was, in fact, a Sea Queen in the same timeframe. A barque built of teak in Howrah, India, in 1841, the Sea Queen carried 170 female convicts to Van Diemen’s Land in 1846 [09]. It did at least three emigrant runs from London to Port Adelaide in 1851, 1855, and 1856, and a run from Launceston to Port Adelaide in 1850 [10]. In 1853, the Sea Queen voyaged from Melbourne to Singapore, leaving on 28 May and arriving on 13 July. It is possible that the Sea Queen was back in Launceston at the end of 1853 and was the ship that Jim made his escape on. There was also another candidate Sea Queen. A 134-ton schooner, it arrived in Hobart on 10 December 1853 after leaving Melbourne seven days earlier. More research is needed to identify the ship that he may have escaped on.

He definitely came to the Australian colonies on the Ocean Queen. The simplest solution is that he confused the names of the ships four years later (perhaps due to his Chinese language not differentiating between “ocean” and “sea”), but perhaps he travelled on both the Ocean Queen (in 1844) and the Sea Queen (in 1853)!

Ovel to James Ovel to Jim Taker

1855: Colony of South Australia

Jim married Ellen Farrell (or O’Farrell) in Adelaide on 6 February 1855.

We now meet James Ovel.

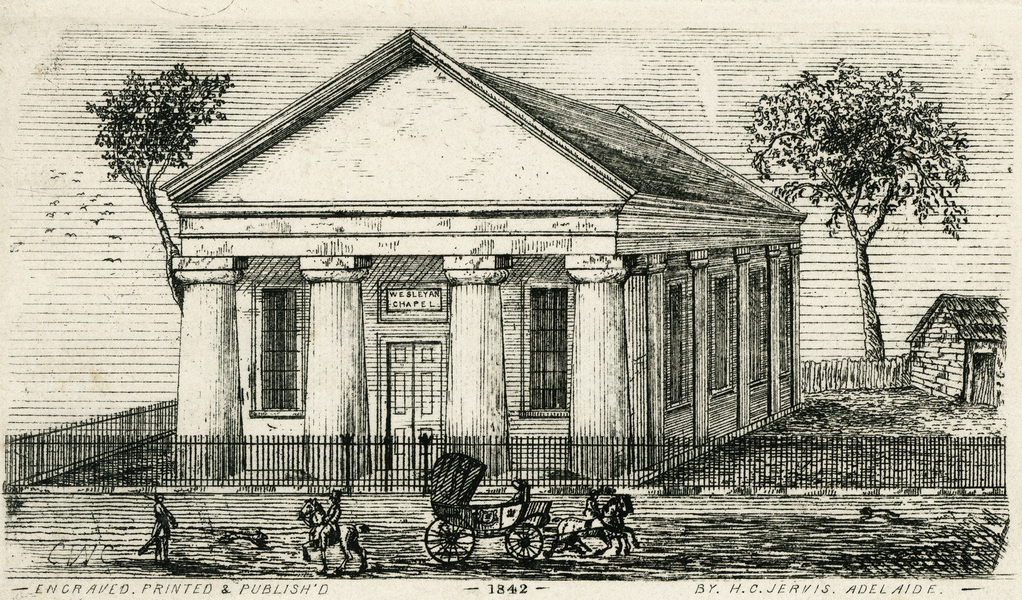

Whatever the circumstances of Ovel’s escape, he was certainly in Adelaide by the beginning of 1855. As James Ovel, he married Ellen Farrell at the Wesleyan Mission House in Gawler Place, Adelaide. The celebrant was Joseph Dare – the Wesleyan minister – and witnesses were William Lewis and Daniel Ellison. Unfortunately, many of the details about the couple were not recorded on the marriage registration: places and countries of birth, residences, and names of fathers. James is identified as a cook and a 27-year-old bachelor. Ellen is a 28-year-old widow.

The marriage registration is our link between Ovel the convict and Jim Taker. In 1863, Ellen registered the birth of their daughter, Elizabeth Ann – though the family surname is recorded as Teker and Ellen’s as O’Farrell (“Farrell” in nearly all other documents). The father is James Teker, 40, a cook from Singapore and the couple married in Adelaide in February 1855. Confirmation that we have the right marriage registration.

Nothing is known about how James and Ellen met. James had apparently made it to Adelaide at the end of 1853 after absconding from Van Diemen’s Land. His identification as a cook on the marriage registration suggests that he had found work in the trade he had learned working for John Webb. His age is a little young as he was probably about 33 at the time.

Ellen in 1866 claimed to have arrived in Adelaide in 1854 on the Teignmouth Castle. There was, in fact, a Taymouth Castle that operated as an emigrant ship, including two voyages from the United Kingdom to Adelaide under contract from the South Australian government in 1854 and 1855. The Taymouth Castle was a three-masted ship of 604 tons, completed in 1851 by Scott and Sons at Greenock on the Clyde, near Glasgow in Scotland. It was later declared lost in November 1861 on a voyage from Columbo to London.

The timing of the Taymouth Castle’s 1854 voyage fits. The ship had departed Plymouth under Captain Adam Logan on 7 February 1854 and arrived at Port Adelaide on 3 May 1854 as an emigrant ship for the South Australian government. There was strong demand at the time for domestic servants and of the 291 passengers, 116 were single women. The passenger list included three Farrells and one O’Farrell. The Farrells were Mary, 23, Julia, 19, and Catherine, 17, presumably sisters. They are listed as servants born in England. Kate O’Farrell, 18, was a servant born in Ireland. All are too young for our Ellen Farrell, who gave her age as 28 at the marriage. She was said to be 80 when she died in 1905, so she probably was 28 or 29. In 1862, there was a newspaper report (see below) of a Catherine Taker of Little Bendigo, wife of John Taker, who I strongly suspect are our Jim and Ellen, so it possible that she was the Catherine or Kate on the Taymouth Castle passenger list.

But a widow? If this was true, she would almost certainly have re-married using her married surname. She certainly seems to have been Farrell, though, as her death certificate lists her parents as James Farrell and Ellen Farrell, née Kelly, and that she was born in Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland.

Why the Wesleyan Chapel? Ellen was almost certainly Roman Catholic and indeed was buried as such in 1905. There is a clue in Jim’s 1857 prison record where he states that he is Protestant. Documents in Van Diemen’s Land have his religion as “Chinese” and the later record of one of his aliases has “Heathen.” As we have no idea when he started using the name “Jim” or “James,” it is possible that he was baptised James as a Baptist in Adelaide prior to the wedding. It does seem strange that he was still using the name “Ovel” when this was the name he was known by as an escaped convict.

I suspect that he only used “Jim.” The more formal “James” seems only to have been used on records that Ellen was involved with.

Or perhaps it was just that Joseph Dare, the Wesleyan minister, was more tolerant of a Chinese man marrying a European woman.

He had taken up the name Jim Taker by 1856 at the latest when he and Ellen had moved to Little Bendigo, near Ballarat [11]. And this is what we shall call him for the rest of the story.

Little Bendigo

1856: Colony of Victoria

Jim and Ellen’s first child – Victoria Julia – was born in Little Bendigo on 13 March 1856 [12].

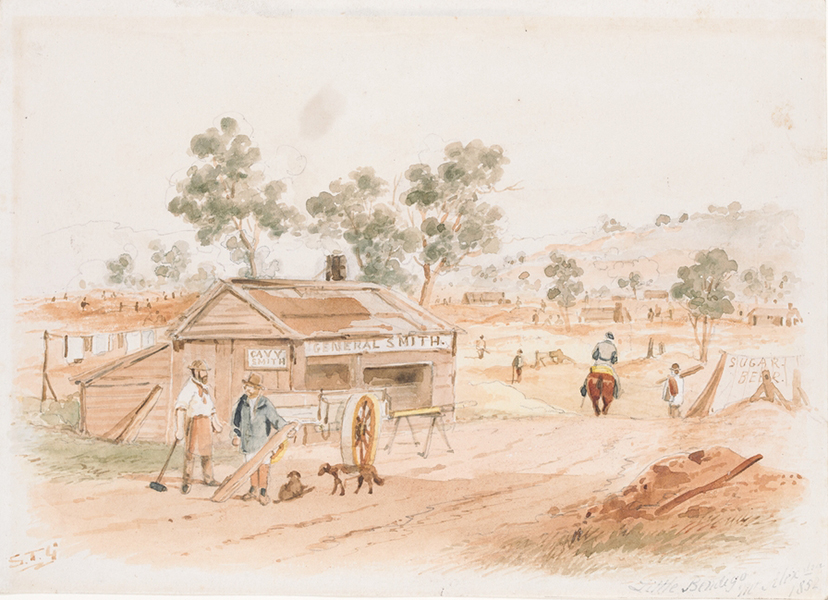

By early 1856, the couple had moved to Ballarat to the Little Bendigo Chinese village, where the family lived for a number of years and most of their children were born. Little Bendigo, to the north-east of Ballarat and now the suburb of Nerrina (and often confused with the Little Bendigo Chinese village that existed briefly near Castlemaine), was very much a tent town and home to mainly people from Amoy (Xiamen). The vast majority of Chinese on the Victorian gold fields were from the districts around Canton (Guangdong). Being from Amoy, Jim would have heard about Little Bendigo as a place for people who shared his dialect and customs, though it had been about 16 years since he had been home.

During May 1856, Jim was appointed the headman of the village by the Chinese Protector for the Ballarat Gold District, William Henry Foster . He was in this role until August at a monthly salary of £10. He accordingly appears in the Fortnightly Warden reports for the Ballarat Gold District for 10 May, 24 May, 7 June, 21 June, 5 July, 19 July, and 2 August 1856. These reports also show that the role had been vacant for several months prior to Jim’s appointment. They also show that the village’s population fluctuated between 300 and 500 people. Jim, ever the opportunist, would have seen an opportunity to make some money, without having to search for gold, and gain some influence, though the Government-appointed headmen of the villages were generally viewed with suspicion by both the Government officials and the denizens of the villages.

[More on the Chinese Protectors and Chinese Villages to follow.]Although we know nothing of his “extra-curricular” activities between 1853 and 1856. The next stage of Jim’s story is that of a career criminal – in and out of prison.

He was soon in trouble ij Little Bendigo and it appears to have cost him his job as headman, as the role is vacant in the 16 August report. An incident in the Little Bendigo village on the 16th of August led to a series of court appearances. He was arrested on either the 16th or 17th and appeared before William Turner , the Stipendiary (Police) Magistrate, at the Ballarat Police Court on 18 August 1856.

The prisoner was committed to take his trial at the next Sessions; the Bench intimating that they would take bail for his appearance [15].

Jim is mentioned twice in William Henry Foster’s correspondence book, though Foster indexes him as Jim Yaker.

Prison

1857: Colony of Victoria

Jim and Ellen’s second child – Mary Ann Edith – was born on 4 March 1857.

In April 1857, Jim had several court appearances, culminating in a trial. On 6 April, he appeared before Warden James Daly , JP, (Warden of the Gold Fields); William Henry Foster , JP, (Chinese Protector); and S Irwin, JP. He was charged with having violently assaulted William Hay, a storekeeper on Bakery Hill in Ballarat. After testimony from Hay and two other witnesses, Taker was remanded until the following day [19].

The next day, he appeared before Charles Wale Sherard , JP, (Resident Warden for the Ballarat Gold Fields District) and Gorges Macdonald Lowther , JP, (Warden of the Gold Fields and Police Magistrate). Additional testimony was heard and Jim was committed to trial at the Circuit Court [20].

The Circuit Court trial took place on 25 April 1857, before Mr Justice Robert Molesworth and a jury of twelve [21].

The prosecutor was cross-examined by Mr Trench, and denied that he ever struck the prisoner.

Thomas Smith deposed, he was a miner living next door to the prosecutor. He heard him scream murder, on the night of the 4th of April. He ran to his assistance, and met the prisoner running away. He had watched the prisoner for two hours. When near the Church of England, the prisoner snapped a pistol at him. Witness still pursued the prisoner, and took him back to Mr Hay’s store. Witness afterwards picked up the pistol now produced.

Cross-examined by Mr Trench – The pistol turned out not to be loaded. The prisoner did not appear to have received a black eye.

Edward Thomas Compton gave similar evidence to the previous witnesses.

Dr Allison proved that he was called in to attend upon the prosecutor, who had received a severe wound, which had been inflicted by some blunt instrument, such as a hammer. The wound was a serious one, and likely to do serious bodily harm. One of the arteries was much injured.

Constable Burke proved that he arrested the prisoner who had no black eye at the time.

Mr Trench addressed the jury for the prisoner, and said his client had a quarrel with the prosecutor about the quality of a nobbler, when Mr Hay struck him in the eye with a bottle, and then the blow with the hammer was given. Mr Trench called several witnesses as to character, but on cross-examination it was elicited that Jim Taker had been tried and acquitted for firing at a Chinaman some little time ago.

The jury found the prisoner guilty, and he was sentenced to five years upon the roads [hard labour].

The remainder are landed daily, and are employed in constructing a wharf, and otherwise in improving the harbor at Williamstown. The expense of supervision is, for twenty-seven officers, five thousand six hundred and eighty-three pounds ten shillings.

Jim was apparently in the latter category during his six weeks on board the Success. These convicts were lodged in cabins between the ship’s decks and which could hold anything from two to twenty prisoners. Jim was soon transferred to the Prison Hulk Sacramento on 30 June. This date is significant in that it was when all of the remaining prisoners on the Success were transferred to the Sacramento. Jim was also one of the prisoners then transferred to the Prison Hulk Lysander on 17 September. On 23 December, he was transferred to Pentridge Stockade, where he stayed for four months [23].

Jim’s prison record gives a full description: Height – 5 foot 3 3/4 inches; Yellow complexion; Black hair; Dark brown eyes; Flat nose; Large mouth; Sharp chin; Scanty eyebrows; Square visage; Low forehead. He had a scar between the forefinger and thumb on the left hand and a scar on the left arm. His “native place” was China, he was a cook, Protestant, and could read and write in Chinese. The latter is interesting in that it suggests that he was literate in Chinese before coming to Australia, so not just a peasant from Amoy. Indeed, he signed his name in Chinese characters as “Cheong Tak” on the court record of his testimony in 1857 [24].

1858: Colony of Victoria

Jim was transferred to Her Majesty’s Collingwood Stockade on 30 April 1858. On 8 July 1858, he was given twenty days in solitary confinement for disorderly conduct.

1859: Colony of Victoria

Ellen gave birth to a third child – James – apparently during 1859.

After serving two years of his five year sentence, Jim was issued with a ticket-of-leave. This allowed him to return to the Ballarat District (and nowhere else) to live and work. Initially introduced for transported convicts, the system was continued for Australian prisoners. The prisoner had to have the ticket-of-leave with him at all times. If he failed to produce it, he was considered a prisoner of the Crown and returned to Government service. The application for the ticket-of-leave was on 21 April 1859, authority granted 16 May, and issued on 20 May 1859. He presumably returned to Ballarat.

Jim was in prison from May 1857 to May 1859, so could not have been the father of a child born during 1859. James Taker (junior) was actually the son of Constable Christopher Molony, who presumably had some sort of liaison with Ellen Taker while Jim was in prison. Molony had been assigned to support the Chinese Protector William Henry Foster [25]. In 1865, Ellen sued Molony “for neglecting to support an illegitimate child.” By 1865, Molony had retired from the police force and ran a hotel. Molony was brought from Batesford, near Geelong, for a court appearance. Appearing before the Police Magistrate (probably Stephen Thomas Clissold ) and Mr McKean, JP, at the District Court on 21 February:

1860: Colony of Victoria

Jim and Ellen’s fourth child – Ellen – was born during 1860.

On 13 February 1860, authority to issue a Certificate of Freedom for Jim was granted and it was issued three days later. A Certificate of Freedom is usually issued to a prisoner at the end of his term but this was issued after less than three years.

1861: Colony of Victoria

Back in court again, Jim appeared before Stephen Thomas Clissold , Police Magistrate, and S Wilson, JP, at the Eastern Police Court on 18 November 1861.

First: That Jim Taker, now a prisoner in Her Majesty’s Gaol at Ballaarat in the said Colony of Victoria is charged with having on the eighteenth day of November AD one thousand eight hundred and sixty feloniously and burglariously entered the store of Helen Durham of Beaufort in the said Colony widow and stole therefrom a piece of cloth a piece of Calico four pairs of Bedford cord [unreadable] twelve pairs of cloth trousers one pair of moleskin trousers a [unreadable] two shirts and forty pounds of tobacco of the goods and chattels of the said Helen Durham.Second: That the said Jim Taker is now committed for trial for the above offence.

Third: That it is necessary that the said Jim Taker should be brought before the Court of General Sessions to be holden at Ararat in the said Colony on Friday the thirteenth day of December AD 1861 for the purpose of being tried for the said offence.

1862: Colony of Victoria:

Jim and Ellen’s fifth child – Elizabeth Ann – was born on 25 June 1862.

Elizabeth Ann’s birth registration is the only one I have found of the six children.

There was an interesting case before Stephen Thomas Clissold , Police Magistrate, and R J Hobson, JP, at the Eastern Police Court, Ballarat, on 7 April, 1862.

1863: Colony of Victoria

At the Eastern Police Court before Stephen Thomas Clissold , Police Magistrate, on 11 February 1863 [30].

Jim and Ellen’s sixth child – Edward – was born during 1865.

In October 1865, Jim seems to have taken off. He was:

1866: Colony of Victoria

Whilst Jim Taker was “missing in action,” Ellen appeared in court on 11 April 1866 charged with vagrancy. She and five of her children were sentenced to six months in gaol – and James was sent to his father, Christopher Molony. They were transferred on 30 April to the Prison Hulk Success, where Jim Taker had been incarcerated briefly in 1857. The six-month sentence would have taken them to October, but authority to release them all early was granted on 23 July 1866. They were actually released on remission on 10 August. In October, Ellen and her children were back in court. She took three of the children to an appearance at the Police Court where she asked for them to be cared for as she was unable to support them. She was given 10/- from the poor box and told to bring the children to court the following Monday for a decision. The children were sent to Industrial Schools.

[More details to follow.]1867: Colony of Victoria

Back in court again on 15 April. Jim is charged with having deserted his family “several years ago”. He testified that:

Jim’s claims here seem to tie back to the prison term of Ah Coe (see below), so Pentridge, another name… Two weeks later, he was called to court where he stated that he had “squared” matters with his wife. The charges were dropped and the case dismissed [35].

Ah Coe, alias Ah Tick?

Now, the interesting thing here is that Jim Taker’s prison record from 1857 (No 3464) has a note saying that he was reconvicted as No 7433. The prison record for No 7433 notes that this prisoner was previously convicted as No 3464. The complication is that this latter record is in the name Ah Coe, who was convicted in Eagle Hawk (Eaglehawk, near Bendigo) before Police Magistrate Graham Webster on 27 November for being “on premises armed with offensive weapons with felonious intent.” Ah Coe was sentenced to two years hard labour and was at Pentridge from 19 December 1865 and the Prison Hulk Sacramento from 9 August 1866 until remission on 30 March(?) 1867. This same prison record notes another conviction in September 1867. Unfortunately, there is no indication of when and how the authorities determined that prisoner 7433 was the same person as prisoner 3464 [36].

This does seem to give us an explanation for where Jim Taker was when he was said to have deserted his family in October 1865.

1867: Colony of Victoria

The second conviction was for larceny on 25 September 1867. Jim was tried at the Warrnambool Court of General Sessions before Judge Charles Babington Brewer [37]. There is a comment that notes that he was tried as Ah Tick. He was found guilty, sentenced to three years, and was back in Pentridge from 29 October 1867 and the Sacramento from 14 May 1868. He was released on remission on 12 July 1870. A third conviction in 1868 is also recorded on the page but apparently didn’t apply to him as it has been crossed out.

Ah Coe’s description is a bit different to Jim Taker’s: Height – 5 foot 4 inches; Fresh complexion; Black hair; Brown eyes; Medium nose; Medium mouth; Medium chin; Black eyebrows; Oval visage; Medium forehead. His “native place” was Shanghai, he had no trade, was Pagan, and could neither read nor write (English). His age is recorded as 35 in 1865, so born in 1830. Now this sounds like a different person. It is only that the prison records link Jim Taker in 1857 to Ah Coe/Ah Tick in 1865-1867 and that does tie in to Jim Taker claiming to have been in Pentridge under “another name”, though Eaglehawk is quite a distance from Castlemaine. Ah Coe and Ah Tick are much more common Chinese names in Australia during this period, so it may be difficult to take this further.

Assuming the Ah Coe/Ah Tick story is true, Jim was apparently back in Little Bendigo from July 1870 to August 1873, before disappearing again.

There is an Ah Tick who was tried for larceny in Taradale on 9 October 1871 and sentenced to two months in Castlemaine Gaol. He is described as a Chinese miner, born in 1826, 5 foot 4 inches tall, sallow complexion, black hair, brown eyes, long nose, large mouth, medium chin, and “Slight build, scar right side of forehead, scar right side of head, tip of right third finger injured, high cheek-bones, large nostrils” Almost certainly not our guy [38].

Back to Jim Taker

Elizabeth Ann Taker died at the Ballarat Industrial School on 23 May.

1873: Colony of Victoria

By 1873, the family was living at Browns Diggings and using the surname “Teager.” Jim’s two eldest living daughters – Julia (Victoria Julia) and Mary (Mary Ann Edith) – married Chinese storekeepers from Amoy on 15 April 1873. Julia married Ah Hiah, also known as John Williams, and Mary married Hansan.

1875: Colony of Victoria

Jim and Ellen’s third daughter, Ellen, married Lew Kim, a Cantonese storekeeper, on 28 July 1875. The family was living on Smythesdale Road, near Smythesdale , about 19 kilometres south-west of Ballarat. Lew Kim was from the “Chinese Town near Smythesdale.”

Jim Taker had apparently disappeared not long after the marriages of Julia and Mary in 1873. He was charged on a warrant issued by the Smythesdale Bench on 21 September 1875 with deserting his wife since August 1873. It would seem that he was around for the dual wedding of Julia and Mary. “James Taker” is described as:

Soon after, the Lew Kims and Ellen Taker/Teager were living in Haddon, about 12 kilometres south-west of Ballarat and a few kilometres north of Smythesdale.

A Reappearance?

It is worth noting that there is a prison record of an Ah Tick, alias Ah Tip, who was incarcerated five times in Victoria between 1880 and 1885. He is described as 5 foot 1 1/2 inches tall and born in Canton in 1853, so this appears not to be our Jim Taker/Ah Tick [40].

So, court cases and incarceration in the Wagga Wagga Gaol point us at the Narrandera and Wagga Wagga Chinese villages.

If he was based in Narrandera, he would almost certainly have been living in the Narrandera Chinese Camp and, given his description as “a cook and general station hand” in 1875, he may have been working at a station near Narrandera – as well as his extra-curricular activities. Similarly the Wagga Wagga Chinese Camp if he had been based there.

Police Sub-Inspector Martin Brennan and the merchant Mei Quong Tart had visited the Narrandera, Wagga Wagga, Hay, Deniliquin, and Albury Chinese Camps in 1883 as part of an inquiry requested by the Inspector-General of Police for New South Wales, Edward Walcott Fosbery , and approved by the Colonial Secretary, Alexander Stuart . The report was tabled in the New South Wales Parliament in January 1884 [41].

The camp at Wagga is next in importance; it occupies a position on each side of Fitzmaurice-street, on the banks of the Murrumbidgee; the land and houses are leased and let similarly to those at the Narrandera camp; it contains two lottery houses, fan-tan rooms, ticket-sellers’ houses, stores, cook-shop, &c. The total population of the camp is 223, that is, 194 Chinese, six European married women, one Chinese married woman, sixteen children, and seven prostitutes. The Chinese gave their calling as twelve in stores, thirteen in opium-shop, thirty gardeners, six proprietors of lottery-rooms, six fruit dealers, and 124 labourers and ticket-sellers.

The Wagga Wagga Advertiser reported that Jim Taker had taken Che Sang to court on an assault charge. Appearing before James Gormly , Mayor of Wagga Wagga and Justice of the Peace (JP), and Alexander Thorley Bolton , JP, at the Wagga Wagga Police Court (at the Wagga Wagga Court House) on 15 May 1885, Taker testified that he had entered Che Sang’s house a week earlier. He knew it to be a gambling house and noted that there were two men playing cards. Che Sang found him and literally kicked him out. Che Sang testified that Taker has caused a fuss, so he was removed but not kicked. Te Yong Hap corroborated Che Sang’s story and the Bench dismissed the case [42]. As the case was heard at the Wagga Wagga Police Court, it would seem that Che Sang’s gaming house was at the Wagga Wagga Chinese Camp. Narrandera had its own Police Court and is about 100 kilometres away.

1887: Colony of New South Wales

This Jim Taker was arrested two years later. We don’t have the details of the initial court appearance, but it would seem that Jim appeared before the Narrandera Police Court at the Narrandera Court House in July 1887 on two charges. For the first – possession of an electroplated tray “reasonably supposed to be stolen, and for which he could not satisfactorily account” – he was found guilty and sentenced to three months’ hard labour at Wagga Wagga Gaol. The second charge was a felony. He pleaded not guilty but was committed for trial at the Wagga Wagga Circuit Court in September 1887. He was identified as “Ah Taker alias Jem Taker (Chinaman)” in the New South Wales Police Gazette [43].

The Wagga Wagga Advertiser report of the September trial [44] refers to him as “R Taker, alias Jim Taker (a Chinaman),” which probably represents what the reporter heard rather than what the police recorded. This may not be our man, but it certainly sounds like him given the uniqueness of the Jim Taker name and the nature of the crimes. The New South Wales Police Gazette Index for 1887 lists him twice “Ah Taker, alias Jem Taker” (under “A”) and “Jem Taker, alias Ah Taker (Ch)” (under “J”). As the latter entry is listed with the “J” surnames it is presumed by the authorities to be the Chinese form “Jem Taker”. The “Jem” was probably a corruption of “Jim.” “R Taker” = “Ah Taker?” [45].

As reported by the Wagga Wagga Advertiser, Jim appeared before Sir George Innes , Justice of the NSW Supreme Court, at the Wagga Wagga Circuit Court (at the Wagga Wagga Court House) on 26 September, charged with “being found at night with intent to commit a larceny.” Constable Charles Birch of the Narrandera Police testified that at 2:30am on the morning of 16 July 1887, he found Taker standing on the verandah of Ferrier’s store in Narrandera, outside the millinery section. Alerted by what he thought was the sound of someone pushing against a door, Birch struck a light and accosted Taker, who denied that he was there with “an improper object.” Even though there were no marks on the door, Birch took him to the Narrandera lock-up and charged him.

Cross examined by Taker – as was the custom in those days – Constable Birch stated:

Jim’s acquittal was recorded in the Register of Criminal Indictments [46]. One wonders how it was that Jim was in Narrandera only two months into his three-month sentence on the possession charge of July. Even though the quoted exchange in court is brief, it is worth noting that: Jim spoke reasonable English; the Wagga Wagga Advertiser reporter did not feel the need to “pidginise” Jim’s comment; and that Jim was still a “smart arse.” It is also notable that a Chinese man with “form” – and we don’t know whether the court also knew of his Victorian criminal record – was acquitted.

Robert Pitcairn , the Crown Prosecutor in Jim’s case, died of tuberculosis and bronchitis on 29 September 1887, just three days after Jim’s trial. He had been a Police Magistrate and Warden of the Gold Fields in Victoria in 1875 to 1878, before moving to New South Wales and taking up the role of Crown Prosecutor for the South-Western District of the Courts of Quarter Sessions.

Unfortunately, none of the 1885-1887 documents so far give a description or indicate Jim’s age. Our Jim Taker would have been between 60 and 65 in 1887.

The trail goes cold at this point. He would have been returned to Wagga Wagga Gaol to serve the remainder of his sentence – with a possible extension – and would have been released in October or November 1887. Did he return to the Narrandera or Wagga Wagga Chinese Camps? I do not have any references to his ultimate fate or what he may have been doing between 1873 and 1885.

Jim presumably did not live much beyond 1887 and probably died in New South Wales, but that part of the story is still unknown.

Footnotes

| 01⇧ | Pauline Rule, “Notes on Jim Taker,” 8 August 2018. So many thanks to Pauline for her notes that provided so much information and opened up the vistas for further research about Jim and his family. |

|---|---|

| 02⇧ | Victoria Police Gazette, 21 September 1875, p 216 [Ancestry (Membership required), 4 April 2024]. He was reported as 54 by the police in 1875 (so 1821), 43 by the police in 1865 (so 1822), 40 by his wife in 1863 (so 1823), and 30 in his 1857 prison record (so 1827). The convict records for Ovel say he was 22 in 1844 (so 1821 or 1822). On the other hand, the prison record of the Ah Coe alias gives his age as 35 in 1865, so born in 1830. The marriage certificate of “James Ovel” has his age as 27 in February 1855, so 1827. |

| 03⇧ | Port Adelaide; Adelaide Observer, 25 November 1843, p 2 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 04⇧ | Shipping Intelligence – Port of Hobart Town; The Courier (Hobart), 5 April 1844, p 2 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 05⇧ | Shipping Intelligence – Port of Hobart Town; The True Colonist (Hobart), 5 April 1844, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 06⇧ | It is worth noting that much of the confusion of Ovel/Orel and Oveil/Oreil was people at the time misreading the handwriting in the relevant documents. |

| 07⇧ | Hobart Town Gazette, 8 November 1853, p 1080. |

| 08⇧ | Hobart Town Gazette, 27 December 1853, Page 1327. |

| 09⇧ | Convict Records – Sea Queen |

| 10⇧ | Passengers in History – Sea Queen (Link dead on 1 February 2024). |

| 11⇧ | One possibility for the origin of the name would be if he was known as “Ah Tak” when he arrived in Australia and either he or someone else started calling him Jim. See also the references to “Ah Tick” later in this article. My other Chinese ancestor arrived in Australia as “Ah Hiah” and used an alias of “John Williams”, later morphing it to William Hiah – and even John William Hiah. I am not sure whether Jim Taker ever used “James” himself as he is always referred to as “Jim” in the many legal and newspaper reports I have. He doesn’t appear to have used Teager/Teaguer himself, either. Not being able to read or write English, he would never have written it, so it seems to have been up to his wife to use James and Teager/Teaguer on official documents and the like. By 1873, his wife and children were using “Teager” on the marriage certificates of the three daughters in 1873 and 1875. This later morphed into Teaguer by 1895 onwards, though there are a couple of references to Ellen and Edward Teaguer in 1880. Perhaps Ellen was trying to make the family look a bit more respectable – and more “white” – though the children are still described as “half-caste”. |

| 12⇧ | I don’t have a birth registration for Julia. The year of her birth is calculated from her age on her wedding registration – 17 – and the date is from her granddaughter’s (my grandmother’s) birthday notebook Golden Truths and Birthday Note Book. Her marriage registration of 1873 records that she was born in Ballarat, as does that of her sister, Mary Ann Edith. Ellen junior’s marriage registration records Little Bendigo. I believe all three sisters were born in Little Bendigo – on the outskirts of Ballarat – and the registration (if any) was in Ballarat. |

| 13⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 19 August 1856, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 14⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 21 August 1856, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 15⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 23 August 1856, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 16⇧ | Court of General Sessions for Ballarat and Buninyong; The Star (Ballarat), 9 September 1856, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 17⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 28 August 1856, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 18⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 4 September 1856, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 19⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 7 April 1857, p 2 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 20⇧ | Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 8 April 1857, p 2 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 21⇧ | Circuit Court; The Star (Ballarat), 27 April 1857, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 22⇧ | Champ, William Thomas Napier; Penal Department – Report of the Inspector General upon the present state of the Penal Department and of his views as to its future management; Parliamentary Paper 1856-1857, No 66a, Parliament of Victoria. [Parliament of Victoria] |

| 23⇧ | Pentridge Stockade was established in December 1850 to take the overflow from Melbourne Gaol. The first prisoners were transferred there in 1851. The stockades held prisoners with shorter sentences or those who had been on the hulks. Construction of the permanent penitentiary began in 1858 as a result of a strategic review of prison requirements – largely triggered by Champ’s report to Parliament – and a response the public outcry about the insecure stockades and conditions for prisoners. |

| 24⇧ | Taker, Jim, No 7433, 3464; Central Register for Male Prisoners, Volume 5, Prisoner Numbers 2824-3590, p 641 (Series VPRS 515) [Public Record Office Victoria, 4 April 2024]. |

| 25⇧ | There are a couple of alternate spellings of Molony’s surname in the sources, but Molony is correct. |

| 26⇧ | Police, District Court; The Star (Ballarat), 22 February 1865, Supplement, p 1 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 27⇧ | Reconstructing Jim Taker’s timeline showed that he could not have been the father of James. James appears on Elizabeth’s birth certificate of 1863 where he is listed as “James, 4”. The discovery of this newspaper reference to Christopher Molony fits. James Molony Teager became a bookmaker and died of cancer in 1885. |

| 28⇧ | Eastern Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 19 November 1861, Supplement, p 2 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 29⇧ | Eastern Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 8 April 1862, Supplement, p 1 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 30⇧ | Eastern Police Court; The Star (Ballarat), 12 February 1863, Supplement, p 1 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 31⇧ | ”Jem” is probably a typo, but does reappear in 1887. The Rising Sun Hotel was on Main Street, Ballarat. The source says from 1861-1872, but there are newspaper references to Alexander Young being there in 1857, 1862, and 1863. The license was transferred to a new publican, Michael Hayes, in 1872. There was also a Rising Sun Hotel in Italian Gully, near Smythesdale, operated by George Hatfield in 1862. |

| 32⇧ | News; The Argus (Melbourne), 3 December 1863, p 5 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 33⇧ | Victoria Police Gazette, 21 December 1865, p 470 [Ancestry (Membership required), 4 April 2024]. This entry also references the Victoria Police Gazette for 1859, p 209 (referring to his age as 38 or 39 in 1865; 1861, Page 453 (Housebreaking, so presumably the Durham case); and 1861, p 458 (Ticket-of-leave holders). Unfortunately, these issues of the Gazette do not appear to be available online. |

| 34⇧ | Police, Eastern Court – Family Desertion; The Star (Ballarat), 16 April 1867, p 4 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 35⇧ | Police, Eastern Court – Family Desertion; The Star (Ballarat), 30 April 1867, p 4 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 36⇧ | Ah Coe, (Ah Tick), No 3464, 7433; Central Register for Male Prisoners, Volume 11, Prisoner Numbers 7360-8125, p 74 (Series VPRS 515 P0001) [Public Record Office Victoria, 4 April 2024]. |

| 37⇧ | Brewer at that time was based in Geelong, but also served Warrnambool, Belfast (Port Fairy), Camperdown, Colac, Palmerston (Port Albert), Portland, and Sale, both County Courts and General Sessions. Sale (Gippsland) is in the opposite direction to the rest of Brewer’s territories (along the coast on the western side of Victoria), but he was paid extra for it! Blue Book of the Colony of Victoria 1867, p 34 (VPARL 1868 No 16) [Parliament of Victoria] |

| 38⇧ | Prisoners reported as discharged from the Penal Establishments during the week ending 18th December 1871; Victoria Police Gazette, 1871, p 426 [Ancestry (Membership required), 4 April 2024]. |

| 39⇧ | Victoria Police Gazette, 21 September 1875, p 216 [Ancestry (Membership required), 4 April 2024]. |

| 40⇧ | Ah Tick, (Ah Tip), No 18364; Central Register for Male Prisoners, Volume 31, 17912-18399, p 467 (Series VPRS 515 P0001) [Public Record Office Victoria, 4 April 2024]. |

| 41⇧ | Martin Brennan; Chinese Camps (Reports Upon); in: Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly during the session of 1883-1884, with the various documents connected therewith, Volume 11; NSW Government Printer, 1884, pp 659-666. |

| 42⇧ | Wagga Wagga Police Court, Friday, May 15; Wagga Wagga Advertiser, 16 May 1885, p 2 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 43⇧ | Apprehensions, &c; New South Wales Police Gazette, 27 July 1887, p 234 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 44⇧ | Felonious Intent; Wagga Wagga Advertiser, 27 September 1887, p 3 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 45⇧ | New South Wales Police Gazette, 31 December 1887, pp 1, 15 [Trove, 4 April 2024]. |

| 46⇧ | Supreme Court Register of Criminal Indictments, 1887, p 76 [Ancestry (Membership required), 4 April 2024]. He has been indexed as “June Taker”. |